Hope everyone’s year has been off to a wonderful start! I just got back from my honeymoon in New Zealand, so I’m still adjusting to the toilet spiraling clockwise. It’s a little late, but I’d like to start the new year by looking back at ten things I bumped into in 2025 that felt worth sharing.

- 1) Administrative legibility: When making things measurable makes them worse

- 2) Dunbar’s number and the missing middle of modern life

- 3) Finite vs. infinite games: stop trying to “win” what can’t be won

- 4) Externalizing information: writing as thinking’s exoskeleton

- 5) Black swans and the seductive lie of the bell curve

- 6) The Overton window: politics lags public opinion (and so can markets)

- 7) The Ovsiankina effect: why unfinished tasks haunt you (and how marketers weaponize it)

- 8) Runway numbers: hidden airport detail

- 9) Abbe number: color fringing quantified

- 10) Weddings: Does size matter?

1) Administrative legibility: When making things measurable makes them worse

James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State gave me a vocabulary for something I’ve watched all over medicine and governance: the urge to make reality legible to a central authority. Scott’s book opens with a parable on German scientific forestry. Old-growth forests were hewn down and replanted in monoculture straight rows, so yields could be counted and predicted. The result was a landscape that looked impressively orderly from above (both literally and metaphorically). Yet, these forests proved less resilient over time, because many of the forest’s positive externalities arose from the messy, hard-to-measure parts: biodiversity, soil dynamics, edge ecologies, loss of ancient mycelium, and local uses that didn’t fit neatly in a ledger.

In our eye ER, an example of legibility is the time to “first provider“. While speed matters, when the time it takes to first see a doctor becomes the quality metric of choice, overall patient care can become less efficient. Triages get less comprehensive, physicians suffer from constant interruption, and unnecessary tests can get ordered. Press Ganey scores (a 1-5 scale of patient satisfaction) are even worse when treating patient experience as a proxy for care quality. This is despite the fact that satisfaction can be driven by wait time (which depends on the number of other patients who are having an emergency), the quality of the vending machines, and the perception of care quality (e.g. prescribing antibiotics “just-in-case” for a viral problem). Again, while patient satisfaction matters, Press Ganey scores correlate weakly with objective quality metrics. One large national cohort study has even found that patients in the highest satisfaction quartile had higher total spending and higher mortality (adjusted HR ~1.26).

Legibility isn’t necessarily evil. However, optimizing for easy-to-quantify metrics can be expensive; the system pays in brittleness, perverse incentives, and a slow forgetting of what the numbers don’t see.

2) Dunbar’s number and the missing middle of modern life

Dunbar’s number is a theorized upper limit on the number of people with whom a person can sustain a stable relationship, hypothesized to be between 100-250. This constraint may be a biologic limitation imposed by neocortex size. What really stuck with me this year was Terence Tao‘s observation that modern life seems to revolve around either atomized individuals or huge organizations that we can’t steer. Organizations that operate at or below Dunbar’s number, the “human-scale” middle, are becoming squeezed out to the detriment of social well-being.

This naturally reminded me of Putnam’s Bowling Alone, in which he posited that social capital has been declining in the United States since the 1960s. This mirrors the decline in “third places,” physical spaces for social interactions outside home and work where the middle used to grow. Social media offers a seductive substitute by massifying sociality: you can be “around” thousands of people, maintain weak ties longer, and even feel intimacy through parasocial relationships. Parasociality can provide warmth without reciprocity, and feeds can mimic community without the friction that produces trust. Meanwhile, large organizations can be so gargantuan that individuals feel both less agency and less responsibility for collective decisions, both of which are psychologically jarring.

To me, the missing middle of small groups beneath Dunbar’s number still seems like where belonging, accountability, and purpose actually live.

3) Finite vs. infinite games: stop trying to “win” what can’t be won

James Carse’s distinction between Finite and Infinite Games is wonderfully clarifying:

- Finite games have fixed rules and a winner (sports, career ladders, matching into the “most prestigious” residency).

- Infinite games are played to keep playing (learning, relationships, living a meaningful life).

A lot of modern misery comes from applying finite-game logic to infinite-game arenas. I grew up reflexively treating everything like a finite game: more accolades, better scores, bigger milestones. But the logic of finite games is counterproductive for infinite games. Whether it be friendships, marriage, or finding meaning, “winning” breaks down when one hoards trophies instead of building something together worth inhabiting. The shift I’m trying to make is simple: keep ambition, but aim it at creating possibilities (deeper connection, more curiosity, more generosity, better work) rather than chasing arbitrary finish lines.

4) Externalizing information: writing as thinking’s exoskeleton

After reading Sönke Ahrens’ How to Take Smart Notes, I had to try a Zettelkasten-style system (creating a web of interconnected ideas – I used Obsidian). After a month of excitement, I ran headfirst into the real constraint: high-quality note-taking was far too time-consuming to be practical. Although I didn’t keep up, the attempt reinforced that writing isn’t just storage, but also a cognitive prosthesis.

Externalizing thoughts in writing does several useful things:

- It improves thinking. Once an idea is on the page, you can evaluate it objectively. Flawed or incomplete thinking becomes visible.

- It reduces mental clutter. Instead of focusing on remembering minutiae like in oral societies, our brains can be freed to digest new information.

- It compounds knowledge. Private thoughts die with you; public notes can become scaffolding for other minds.

The irony is that modern life has made knowledge infinitely accessible. With access to nearly every text, everywhere, all at once, attention has turned into the bottleneck. The next step isn’t more information; it’s better filtering and synthesis. LLMs are the obvious first steps. The more interesting possibility is the massive upsides of direct brain-computer interfaces (after all, my former fraternity brother and current Meta Chief AI Officer, Alexandr Wang, has even said publicly that he wants to wait to have kids until Neuralink-like technologies exist). Although I’m unsure whether such a techno-utopian future will be exhilarating or dystopian, I’m certain that less time spent finding information will free up more time for deciding on what’s worth thinking about next.

5) Black swans and the seductive lie of the bell curve

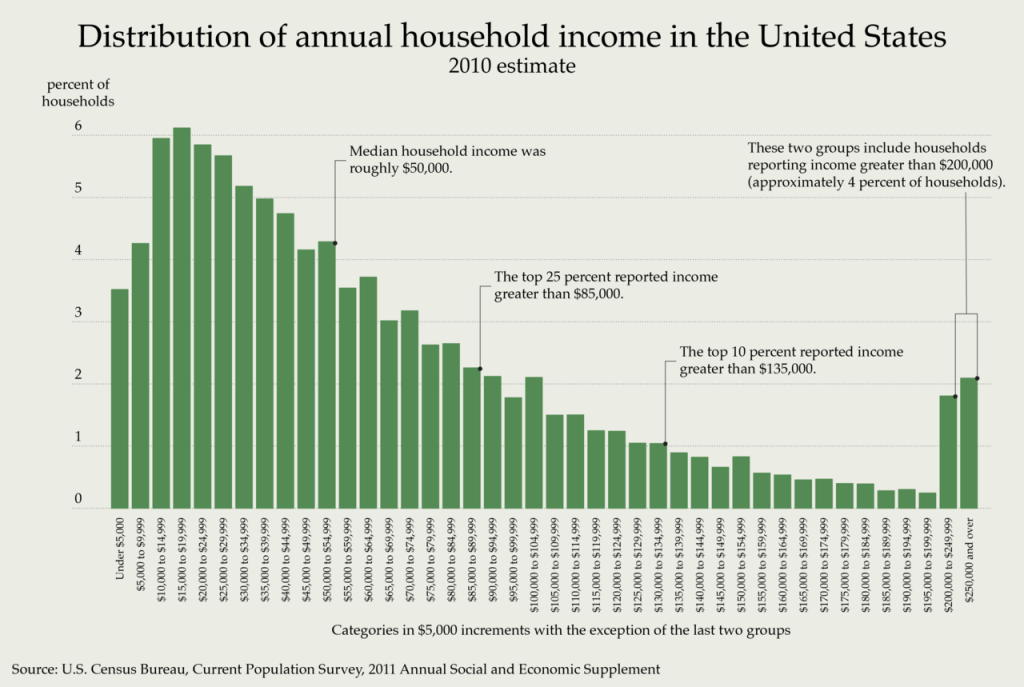

I began reading Taleb’s Black Swan at the same time I came across this Veritasium video. The core insights are essentially the same. First: many physical traits we evolved to intuit (height, shoe sizes) are well-approximated by normal (Gaussian) distributions. Second: many social and complex systems aren’t like that at all; they’re dominated by power laws (think Pareto’s 80/20 rule), where a small number of outcomes account for a huge share of the total. Examples include income, wealth, scientific citations, social-media reach, wildfire size/severity, city sizes, and so on. Third: if we apply Gaussian intuition to non-Gaussian situations, we will systematically underestimate tail risk and be surprised by “impossibly rare” events.

The practical upshot is that we must live with the tails in mind: maximize exposure to positive Black Swans (e.g., making many small but high-risk bets with lots of upside), and minimize dependence on supposedly “low-risk” paths that are actually fragile (e.g., not continuously learning in a“stable” career founded on a single skill set that could be automated).

6) The Overton window: politics lags public opinion (and so can markets)

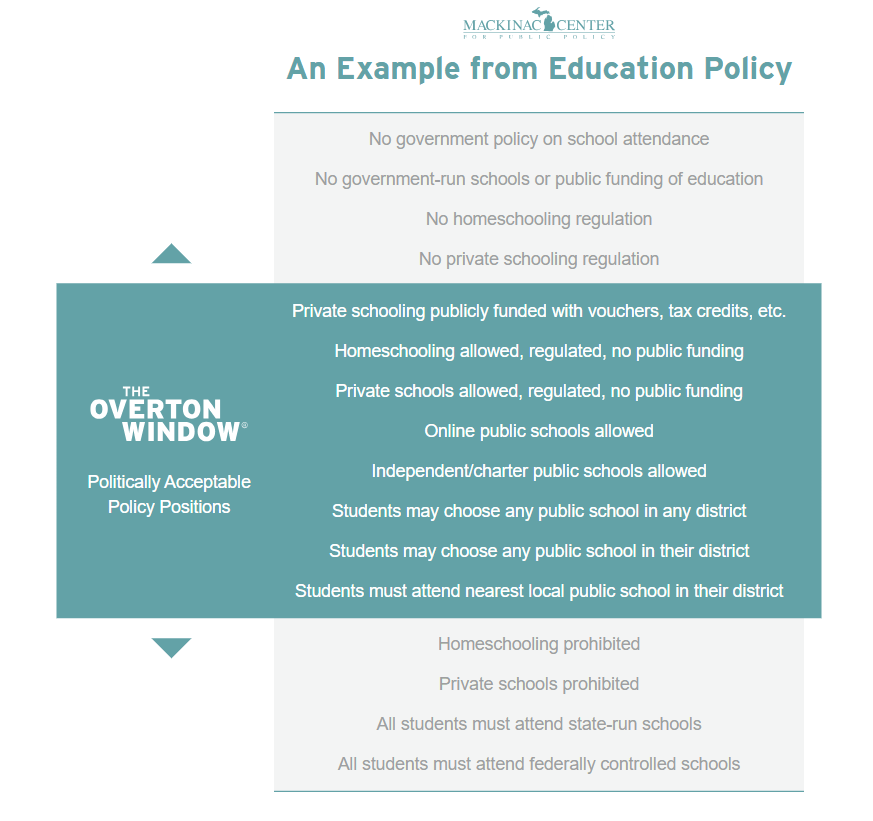

The Overton window is a useful lens with which to view politics. In its simplest form, it postulates that politicians tend to champion ideas that sit inside a socially acceptable band.

The nuance is that there isn’t one window, there are many overlapping ones (primary voters vs. general electorate, party elites, donors, courts, bureaucracies, media ecosystems), and the feasible set of ideas can be multidimensional rather than a single left-right line. Politicians don’t just discover the window; they also shape it through framing, agenda-setting, strategic ambiguity, and coalition-building – sometimes widening what’s discussable, sometimes narrowing it by making alternatives seem unserious or taboo. Think tanks (and movements, unions, religious groups, journalists, etc.) move public opinion less by convincing everyone of a particular position, and more by manufacturing usable ideas: language, moral frames, and research that shift the Overton window and make previously awkward positions safer to hold.

There are echoes of this idea outside of politics, but with the same caveats. Markets have palatability windows, yet those aren’t just consumer taste; they’re shaped by gatekeepers (platforms, distributors), incentives (pricing, risk), and narrative (what feels authentic or trendy). For example, fusion cuisine is akin to a chef trying to craft a commercially successful menu within the window of acceptable options to diners of a local demographic (I think of all the myriad adaptations of Chinese food to local tastes). There’s an ethical analogue too: the set of beings and harms we treat as morally acceptable tends to expand in fits and starts. “Shrimp welfare” sounds like a punchline outside niche circles; however, Effective Altruists are making serious arguments to try to make it part of mainstream moral consideration.

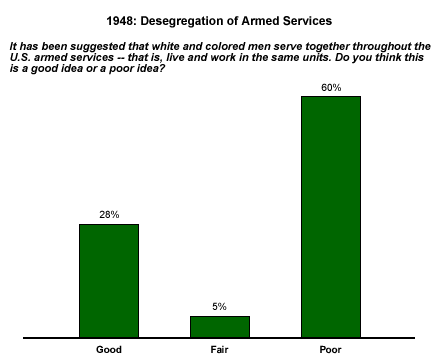

The counterpoint is that leaders sometimes move ahead of public comfort, especially when they can act through institutions insulated from immediate electoral backlash (executive orders, courts, military policy). Truman’s Executive Order 9981 (1948) desegregating the U.S. armed forces is a good example: morally right and supported by internal surveys, yet outside the political mainstream for the time.

7) The Ovsiankina effect: why unfinished tasks haunt you (and how marketers weaponize it)

I spent an embarrassing amount of time in 2025 online shopping for decorations for the wedding. I was also treated to tons of spam along the lines of, “Save 15%—you’re all set to finish booking…,” for services I had definitely not started booking. These marketers were partially leveraging an effect elucidated in the 1920s by Maria Ovsiankina. Briefly, she found that people have a tendency to resume unfinished tasks, even in the absence of external rewards.

Although helpful for task completion, unfulfilled goals can cause cognitive interference. This is not the same as the related concept, the Zeigarnik effect, which postulates that unfinished tasks are more cognitively accessible than finished ones. In his original study, Zeigarnik found that both children and adults remembered interrupted tasks more readily than completed tasks, even when more time was spent on the completed tasks. Although often cited in productivity lore, the Zeigarnik effect looks highly context-dependent, and recent meta-analytic work suggests it’s not a universal law of memory.

Obviously, cognitive offloading (e.g., making to-do lists) is a great way of keeping track of unfinished tasks. However, to further reduce the cognitive interference from unfulfilled goals, plan-making can decrease intrusive thoughts and spillover into unrelated tasks. In other words, making a plan can satisfy the urge to complete unfulfilled tasks. This is especially salient if you are prone to inattention or rumination: open loops may hijack working memory more aggressively, or fragment attention differently, in people with these traits. I’ve tried to apply this to everyday life. On my to-do lists, I not only write down what needs to be done, but also explicitly write down the next needed action. By treating capture as closure (i.e., writing things down as a substitute for inefficient task-switching), I’ve tried to improve my focus on the task at hand.

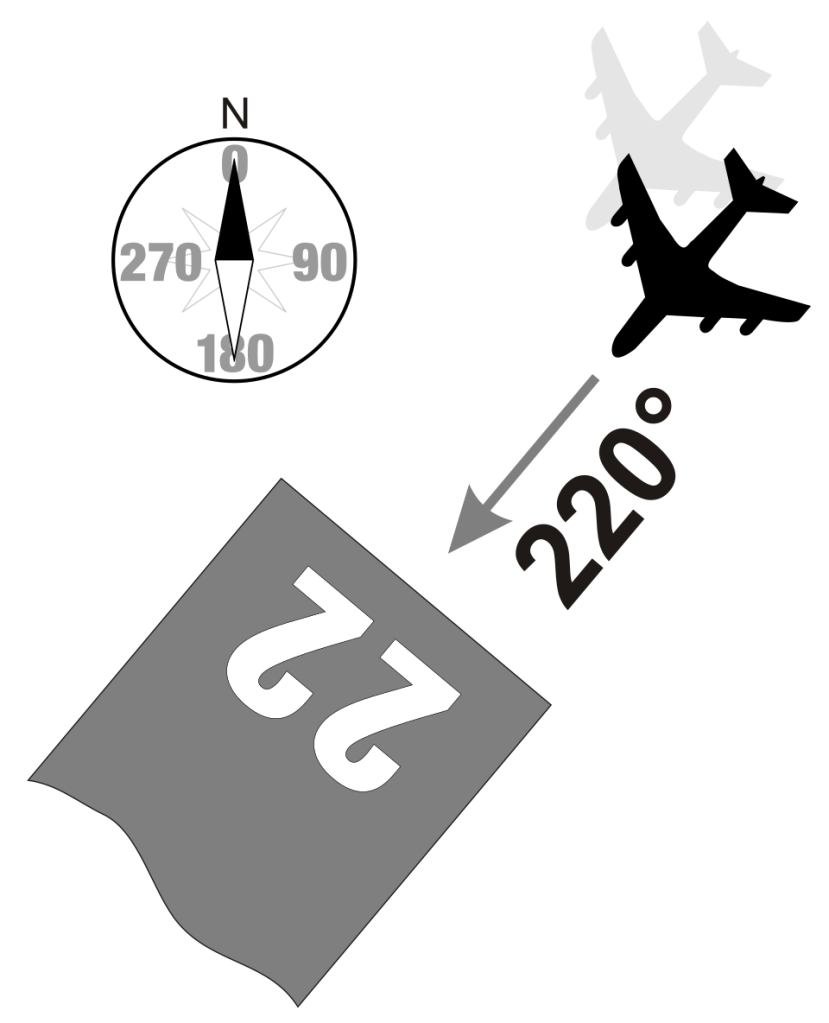

8) Runway numbers: hidden airport detail

While watching planes land in YTZ (Billy Bishop Airport in Toronto) from the comfort of CN Tower earlier this year, my wife wondered aloud about the numbers on the runway. That led us to a delightful CGPGrey video (I’d highly recommend this channel)!

Runway numbers are not arbitrary labels, but a code based on magnetic direction. Each runway is numbered according to its magnetic heading, rounded to the nearest ten degrees, with the final digit dropped. For example, my home airport, PHL has a runway pointing roughly to a magnetic azimuth of 268° is labeled Runway 27 (west, from the perspective of a plane approaching the runway). Its opposite end, 180° away at 88°, points east as Runway 09. To distinguish between parallel runways, airports add the suffixes L, C, or R (for Left, Center, or Right) from the perspective of an approaching pilot.

The keen observer will note that the Earth’s magnetic north is not static. The slow but steady drift of the magnetic north pole means runways’ magnetic headings gradually change over time. When magnetic drift changes the rounded designation, airports repaint the numbers. As airports at high latitudes are most impacted by the drift of the magnetic pole, Canadians have advocated for switching to true north.

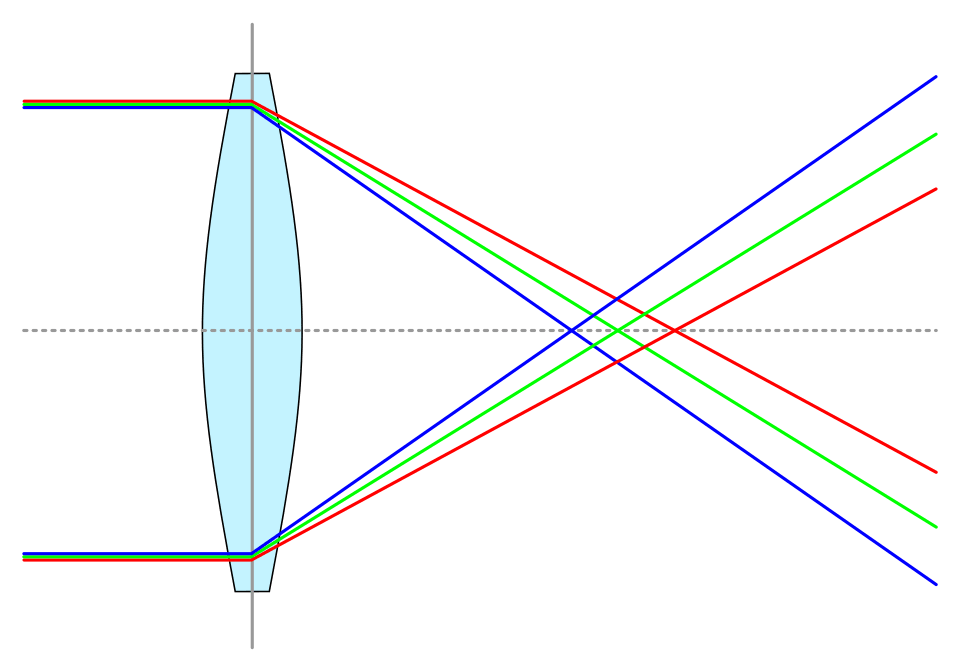

9) Abbe number: color fringing quantified

As an ophthalmologist, I’m ashamed to say I hadn’t gotten new glasses in over 5 years. I finally got a new pair this year and opted for shatterproof polycarbonate lenses. Although I love my new prescription, I was initially quite bothered by little rainbows in my peripheral vision. That led me to read about the Abbe number (V-number), a measure of chromatic aberration. In short, a higher Abbe number = less dispersion = less color fringing.

More formally, the Abbe number, Vd, is defined as:

where nC ,nd, and nF are the indices of refraction at 656.3 nm (deep red), 587.56 (yellow-orange), and 486.1 nm (cyan-blue). For the human visual system, Abbe numbers of less than 40 are clinically noticeable. Polycarbonate has an Abbe number of approximately 30, hence the rainbows. The Abbe number of the natural crystalline lens is approximately 47 and corresponds to almost 1.38D between 450-700 nm. Thankfully, the eye has multiple ways to minimize the impact of chromatic aberration, including macular pigmentation and the distribution of certain types of cones in the fovea as compared to the periphery to correct for blue light being bent more. Functionally, when the eye focuses on mid-spectral wavelengths, most light remains less than 0.25D out of focus, with wavelengths at the extremes of the visible spectrum having lower luminosity.

The Abbe number is an additional parameter to consider when evaluating intraocular lenses (IOLs). Most IOLs have a lower Abbe number than the natural crystalline lens (e.g. Clareon’s is 37). Among commonly used IOLs, only the Tecnis platform has a higher Abbe number (55) (I have no affiliation with J&J). However, the clinical impact of this parameter has been debated, with mixed evidence on the contribution of chromatic aberration to contrast sensitivity.

10) Weddings: Does size matter?

I feel absurdly lucky to have married the love of my life this past August. Wedding planning, however, was occasionally… onerous. After a few hours gluing popsicle sticks to paper fans and burning enough candles for an 1890s séance (in an attempt to keep costs down for my father-in-law), I couldn’t help wondering whether all the prep work was worth it. (Spoiler: yes.)

One crude proxy for “wedding success” is the probability of divorce. This sent me down a rabbit hole on the association between divorce risk and the size/ cost of a wedding. The evidence here is correlational, not causal. However, a frequently cited U.S. study by economists Andrew Francis-Tan and Hugo Mialon surveyed 3,000+ ever-married respondents and found a few interesting patterns (free link here):

- Higher wedding spending was associated with a higher divorce rate. (HR 3.17 for couples spending > $20k vs. couples spending < $1k)

- Lower wedding attendance was associated with a higher divorce rate (HR 12.5 for couples only with no guests vs. >200 guests)

- Other factors that predicted a lower divorce risk: high household income, attending religious services, having a child with one’s partner, going on a honeymoon. Higher divorce risk was associated with a difference in age, a difference in education, and reporting that a partner’s looks were important in the decision to marry.

Of course, these findings probably reflect the wedding as a signal of underlying conditions. Expensive weddings can translate to medium-term financial strain, a situation not helped by rising wedding costs (even r/weddingsunder10k has adjusted the acceptable budget to $20k). Smaller weddings can proxy for constrained resources or limited social support. That being said, while the wedding itself isn’t a magic spell, I can safely say our wedding day was the most magical day of my life.

There’s a lot more to dig into from this paper! I’d highly recommend a close look at Table 3 or this more readable breakdown of other key findings from the paper from the Atlantic.

On that note, wishing everyone a happy 2026! If you’re curious, my 2025 reading and travel lists are below – because I’m incapable of not keeping lists…

What I read in 2025

- How the World Ran Out of Everything — Peter Goodman

- Seeing Like a State — James C. Scott

- White Trash — Nancy Isenberg

- A History of Medicine in Twelve Objects — Carol Cooper

- The Wide Wide Sea — Hampton Sides

- Quality of Vision: Essential Optics for the Cataract and Refractive Surgeon — Jack Holladay

- Cataract Surgery for Greenhorns — Thomas Oetting

- Into the Great Wide Ocean — Sonke Johnsen

- The Order of Time — Carlo Rovelli

- The Country of the Blind — Andrew Leland

- My Family and Other Animals — Gerald Durrell

- The Silk Roads — Peter Frankopan

- Have You Eaten Yet? — Cheuk Kwan

- What the Chicken Knows — Sy Montgomery

- Box Office Poison — Tim Robey

- Grizzly Confidential — Kevin Grange

- More Than Just a Game — Christopher Bjork & William Hoynes

- Millions of Cats — Wanda Gág

- Question 7 — Richard Flanagan

- The MANIAC — Benjamín Labatut

- The Devil’s Element — Dan Egan

- How to Take Smart Notes — Sönke Ahrens

- Everything Is Tuberculosis — John Green

- Atlas of the Invisible — James Cheshire & Oliver Uberti

- Cornea — Christopher Rapuano

- Persepolis — Marjane Satrapi

- When the Air Hits Your Brain — Frank T. Vertosick Jr.

- The Genius of Birds — Jennifer Ackerman

- 21 Lessons for the 21st Century — Yuval Noah Harari

- Bossypants — Tina Fey

- The Let Them Theory — Mel Robbins

- The Omnivore’s Dilemma — Michael Pollan

- The Social Construction of Reality — Peter L. Berger & Thomas Luckmann

- Aflame — Pico Iyer

- Mood Machine — Liz Pelly

- The Invention of Nature — Andrea Wulf

- Puerto Rico: A National History — Jorell Meléndez—Badillo

- 1491 — Charles C. Mann

- Slither — Stephen S. Hall

- The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs — Steve Brusatte

- The Little Book of Hygge — Meik Wiking

- The Gift — Lewis Hyde

- Finite and Infinite Games — James P. Carse

- The CIA Book Club — Charlie English

- Being You — Anil Seth

- The Tyranny of Experts — William Easterly

- The Serviceberry — Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Abundance — Ezra Klein & Derek Thompson

- The Landscape of History — John Lewis Gaddis

- The Cambridge Illustrated History of China — Patricia Buckley Ebrey

- Orbital — Samantha Harvey

- Pride and Prejudice — Jane Austen

- All Consuming — Ruby Tandoh

- Careless People — Sarah Churchwell

- The Black Swan — Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Art Is Life — Jerry Saltz

- A Marriage at Sea — Sophie Elmhirst

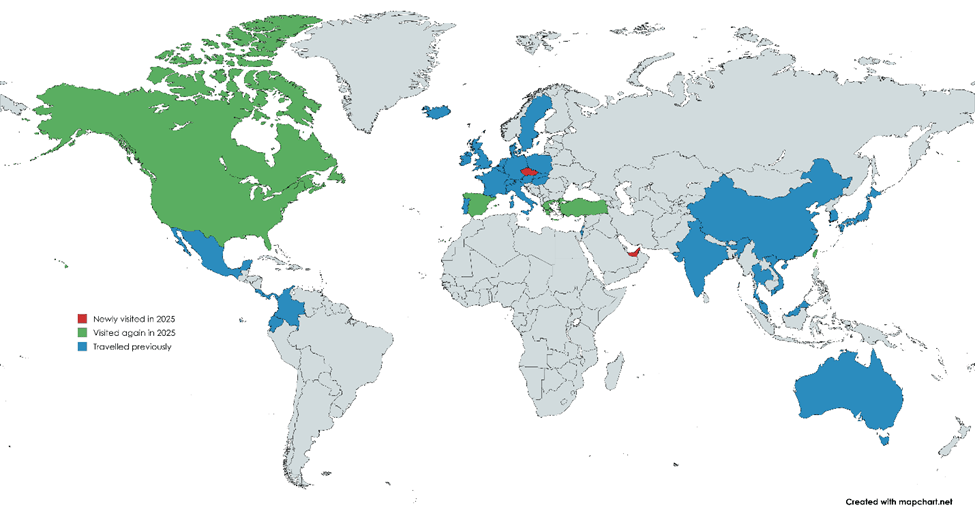

Where I went in 2025

My favorite places to visit were Barcelona (got engaged in the Gothic Quarter) and Nashville (spending Super Bowl Sunday at Robert’s Western World on Lower Broadway + seeing Old Crow Medicine Show playing “Wagon Wheel” at the Grand Ole Opry).

U.S.: California, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia

International: Taiwan (Taipei, Kaohsiung, Tainan, Taichung, Alishan), Canada (Toronto, Whistler), Spain (Barcelona), Czechia (Prague), Greece (Athens), Turkey (Istanbul), UAE (Dubai), New Zealand

Sources

Most sources should already be linked.

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a State. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

- Carse, James P. (1987). Finite and Infinite Games. New York: Ballantine Books.

- https://mathstodon.xyz/@tao/115259943398316677

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Touchstone Books/Simon & Schuster.

- Granovetter, M. (1973) The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360-1380.

- Ahrens, S. (2022) How to Take Smart Notes. Columbia University Press.

- Taleb, N. N. (2008). The Black Swan. Penguin Books.

- Kwan, C. (2022). Have You Eaten Yet? Simon and Schuster.

- https://catalog.archives.gov/id/278080420 (NAID: 278080420)

- Łabuz G, Khoramnia R, Yan W, et al. Characterizing glare effects associated with diffractive optics in presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2024;50(4):413-419.

- Negishi K, Ohnuma K, Hirayama N, Noda T; Policy-Based Medical Services Network Study Group for Intraocular Lens and Refractive Surgery. Effect of chromatic aberration on contrast sensitivity in pseudophakic eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(8):1154-1158.

- Francis-Tan, A., & Mialon, H. M. (2015). “A Diamond Is Forever” and Other Fairy Tales: The Relationship between Wedding Expenses and Marriage Duration. Economic Inquiry, 53(4), 1919-1930.